Blocks

Blocks are batches of transactions with a hash of the previous block in the chain. This links blocks together (in a chain) because hashes are cryptographically derived from the block data. This prevents fraud, because one change in any block in history would invalidate all the following blocks as all subsequent hashes would change and everyone running the blockchain would notice.

Prerequisites

Blocks are a very beginner-friendly topic. But to help you better understand this page, we recommend you first read Accounts, Transactions, and our introduction to Ethereum.

Why blocks?

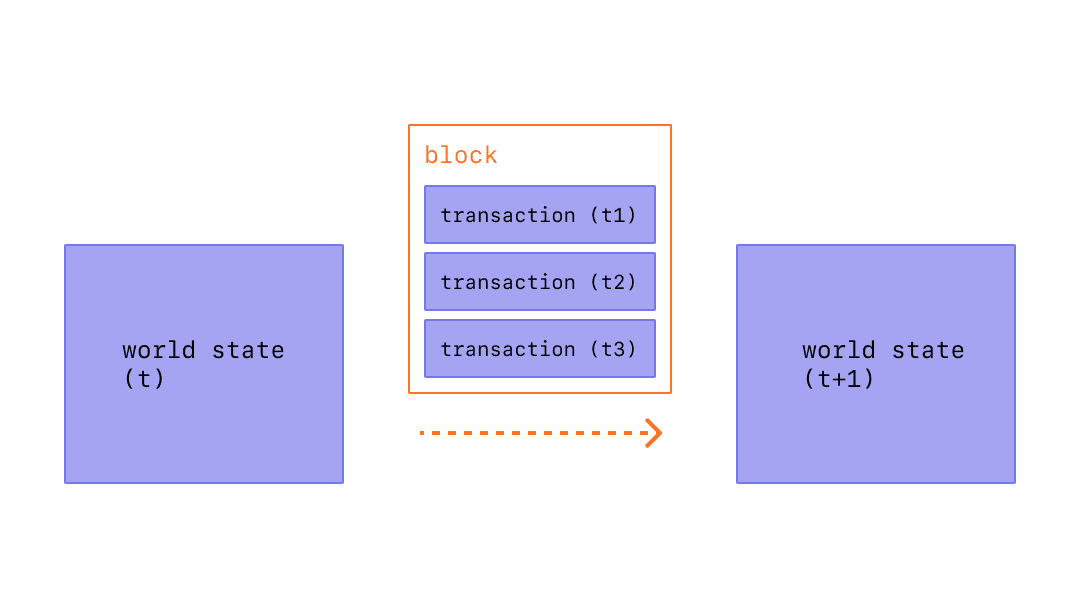

To ensure that all participants on the Ethereum network maintain a synchronized state and agree on the precise history of transactions, we batch transactions into blocks. This means dozens (or hundreds) of transactions are committed, agreed on, and synchronized on all at once.

Diagram adapted from Ethereum EVM illustrated

Diagram adapted from Ethereum EVM illustrated

By spacing out commits, we give all network participants enough time to come to consensus: even though transaction requests occur dozens of times per second, blocks on Ethereum are committed approximately once every fifteen seconds.

How blocks work

To preserve the transaction history, blocks are strictly ordered (every new block created contains a reference to its parent block), and transactions within blocks are strictly ordered as well. Except in rare cases, at any given time, all participants on the network are in agreement on the exact number and history of blocks, and are working to batch the current live transaction requests into the next block.

Once a block is put together (mined) by some miner on the network, it is propagated to the rest of the network; all nodes add this block to the end of their blockchain, and mining continues. The exact block-assembly (mining) process and commitment/consensus process is currently specified by Ethereum’s “Proof-of-Work” protocol.

A visual demo

Proof of work protocol

Proof of work means the following:

- Mining nodes have to spend a variable but substantial amount of energy, time, and computational power to produce a “certificate of legitimacy” for a block they propose to the network. This helps protect the network from spam/denial-of-service attacks, among other things, since certificates are expensive to produce.

- Other miners who hear about a new block with a valid certificate of legitimacy must accept the new block as the canonical next block on the blockchain.

- The exact amount of time needed for any given miner to produce this certificate is a random variable with high variance. This ensures that it is unlikely that two miners produce validations for a proposed next block simultaneously; when a miner produces and propagates a certified new block, they can be almost certain that the block will be accepted by the network as the canonical next block on the blockchain, without conflict (though there is a protocol for dealing with conflicts as well in the case that two chains of certified blocks are produced almost simultaneously).

What's in a block?

timestamp– the time when the block was mined.blockNumber– the length of the blockchain in blocks.baseFeePerGas- the minimum fee per gas required for a transaction to be included in the block.difficulty– the effort required to mine the block.mixHash– a unique identifier for that block.parentHash– the unique identifier for the block that came before (this is how blocks are linked in a chain).transactions– the transactions included in the block.stateRoot– the entire state of the system: account balances, contract storage, contract code and account nonces are inside.nonce– a hash that, when combined with the mixHash, proves that the block has gone through proof of work.

Block size

A final important note is that blocks themselves are bounded in size. Each block has a target size of 15 million gas but the size of blocks will increase or decrease in accordance with network demands, up until the block limit of 30 million gas (2x target block size). The total amount of gas expended by all transactions in the block must be less than the block gas limit. This is important because it ensures that blocks can’t be arbitrarily large. If blocks could be arbitrarily large, then less performant full nodes would gradually stop being able to keep up with the network due to space and speed requirements.

Further reading

Know of a community resource that helped you? Edit this page and add it!